Executive Summary

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represents one of the most significant changes to pharmaceutical pricing policy in recent years, introducing measures aimed at curbing excessive drug price increases. Among its key provisions, the IRA includes measures that require pharmaceutical manufacturers to pay penalties if their drug prices rise faster than inflation under Medicare Part B and Part D.

For pharmaceutical companies, these new rebates present challenges, including direct financial costs, compliance obligations, and potential adjustments to pricing strategies. The rebates apply differently to Medicare Part B, which covers physician-administered drugs, and Part D, which covers retail prescription drugs. Understanding these differences is essential for manufacturers to anticipate financial impacts and ensure compliance. This white paper is designed to provide pharmaceutical manufacturers with a clear understanding of the IRA’s inflationary rebate provisions, their impact on Medicare Part B and Part D, how they compare to state price transparency reporting, and strategic responses to mitigate potential financial and operational challenges. By analyzing the key provisions and discussing practical implications, this paper offers insights to help pharmaceutical companies proactively adapt to the evolving regulatory environment.

Introduction

Context and Background

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, US inflation soared to an average of 8% in 2022. In addition to high inflation, there were also growing concerns over rising prescription drug costs. The Biden Administration signed the IRA into law in August 2022 to address these challenges. The law introduced a series of regulatory interventions aimed at controlling pharmaceutical price inflation. Among these measures, inflationary rebates serve as a mechanism to penalize manufacturers whose drug prices increase at a rate exceeding the Consumer Price Index (CPI). By imposing these rebates, the federal government aimed to stabilize drug pricing and reduce the financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries and the healthcare system.

The introduction of inflationary rebates reflects broader policy efforts to balance drug affordability with industry sustainability. Historically, pharmaceutical companies have had the flexibility to adjust prices based on market dynamics, but the IRA established new constraints that require manufacturers to reassess their pricing and revenue models. The legislation’s impact extends beyond direct rebate payments, influencing supply chain decisions, research and development (R&D) investments, and long-term financial planning.

Relevance for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers

Pharmaceutical manufacturers must navigate this complex regulatory shift while maintaining profitability and innovation. The IRA’s inflationary rebate provisions fundamentally alter the financial landscape for Medicare- covered drugs, prompting companies to develop compliance strategies and pricing adjustments. While the legislation aims to protect consumers and government healthcare programs, it introduces new risks for manufacturers, particularly in the areas of financial forecasting, pricing strategy, and operational efficiency.

Background on Inflationary Rebates

IRA Legislative Overview

The Inflation Reduction Act was signed into law in 2022 with the primary objective of reducing healthcare costs and making prescription drugs more affordable for Medicare beneficiaries. A central component of this legislation is the introduction of inflationary rebates, which require pharmaceutical manufacturers to pay financial penalties if the prices of their drugs increase faster than inflation. This measure is designed to discourage excessive price hikes that contribute to rising healthcare expenditures.

Under the IRA, inflationary rebates apply to both Medicare Part B and Part D drugs, with distinct calculation methodologies for each program. By linking rebate payments to inflation metrics, the policy aims to ensure that drug prices remain stable over time and do not disproportionately burden consumers or the government.

Definition and Purpose

Inflationary rebates function as a financial penalty imposed on pharmaceutical manufacturers when the price of a covered drug increases beyond the established inflation benchmark. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) serves as the key reference metric, determining whether a manufacturer’s price adjustments trigger a rebate obligation. If the drug’s price growth exceeds the inflation rate, the manufacturer must pay the difference back to Medicare, effectively capping price increases to match general economic inflation.

Policy Goals and Intended Outcomes

The primary goal of the IRA’s inflationary rebates is to control the rising cost of prescription drugs and ensure that Medicare expenditures remain sustainable. By discouraging excessive price hikes, the policy seeks to improve affordability for patients while reducing overall federal healthcare spending. Additionally, inflationary rebates are expected to promote price transparency, providing patients and healthcare providers with greater predictability in drug costs.

Detailed Analysis of IRA’s Inflationary Rebates for Parts B and D

Medicare Part B and Part D Overview

Medicare is divided into several parts, with Part B covering physician-administered drugs and Part D covering self-administered retail prescription drugs. The inflationary rebate provisions apply differently to each program, necessitating a detailed examination of their distinct requirements.

Medicare Part B is the portion of Medicare that covers outpatient medical services. This includes doctor visits, preventive care (like vaccines and screenings), outpatient procedures, durable medical equipment, and some home health services. Part B is optional and requires a monthly premium, which may vary based on income. Beneficiaries typically pay 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for most services after meeting an annual deductible. Part B is designed to work alongside Part A (hospital insurance) to provide more comprehensive health coverage for individuals aged 65 and older, or those with certain disabilities.

Medicare Part D provides prescription drug coverage to help Medicare beneficiaries afford their medications. It is offered through private insurance companies that are approved by Medicare, either as standalone plans or bundled with Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans. Part D covers a wide range of prescription drugs, but each plan has its own formulary (list of covered drugs), tiers, and cost-sharing rules. Enrollees pay a monthly premium and, depending on the plan, may also face an annual deductible, copayments, or coinsurance. There is also a coverage gap (commonly called the “donut hole”) where out-of-pocket costs may temporarily increase after spending a certain amount on medications, although recent changes have helped reduce this burden.

Medicare Part B: Inflationary Rebate Provisions

Under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the introduction of inflationary rebates for Medicare Part B represents a significant shift in how pharmaceutical price increases are regulated for physician-administered drugs. These rebates are designed to hold manufacturers accountable for price hikes that exceed the rate of inflation, thereby aligning reimbursement policy with broader cost-containment goals. The provisions apply to single-source drugs and biologicals covered under Medicare Part B, including those furnished in outpatient settings such as physician offices and hospital outpatient departments. Notably, the rebates apply only to drugs that lack generic or biosimilar competition, which limits the immediate scope but signals broader regulatory intent.

Eligibility for inflationary rebates under Part B is defined by several criteria. First, a drug must be a single-source product or a biologic reimbursed under Medicare Part B. A single-source drug is a drug that is produced and marketed by only one manufacturer, and there is no generic equivalent or alternative. Second, the product must be administered in a clinical setting and billed using Average Sales Price (ASP) methodology. Drugs sold through the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) are subject to additional coordination to prevent duplicative rebate obligations. Importantly, the rebate obligation is triggered if a drug’s ASP increases at a rate greater than the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), which serves as the statutory benchmark for inflation. Newly launched products are excluded from rebate liability until a full year of sales history is established.

The inflationary rebate for Part B drugs is calculated quarterly, using the following formula:

Inflationary Rebate Amount = (ASP_current – ASP_inflation-adjusted) × Number of Medicare units sold

Where:

- ASP_current is the drug’s average sales price in the current quarter,

- ASP_inflation-adjusted is the price adjusted for inflation since the benchmark quarter, based on CPI-U, and

- Number of Medicare units sold represents the total units reimbursed under Medicare Part B during the quarter.

The inflation-adjusted ASP is anchored to a baseline quarter (beginning Q1 2023 for Part B) or the first full quarter after market entry, whichever is later. If the current quarter ASP exceeds the inflation-adjusted ASP, the manufacturer must remit the difference multiplied by the number of Medicare units sold during that period. These rebates are paid directly to Medicare and are not passed through to beneficiaries or providers.

Certain exclusions and exceptions apply to mitigate the administrative burden and to focus the policy on high- expenditure drugs. Vaccines and drugs under $100 in annual Medicare spending per individual are generally excluded. Additionally, drugs in shortage or those subject to pricing constraints under government-mandated programs may qualify for temporary waivers or adjusted calculations. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) retains discretion to implement exceptions in cases where rebate obligations may threaten access or affordability.

As it relates to the 340B program, which is a program that allows eligible hospitals and clinics to purchase outpatient medications at discounted prices from manufacturers, CMS has established provisions to exclude 340B drugs. For 340B claims submitted in 2023 and 2024, CMS will exclude units from suppliers that are covered entities under the 340B program. CMS will use a variety of identifiers, including the modifiers “JG” and “TB” on Medicare claims, to help identify and exclude 340B-acquired drugs from the inflationary rebate calculations.

Medicare Part D: Inflationary Rebate Provisions

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) also introduces inflationary rebate requirements for Medicare Part D, aiming to curb excessive price growth for prescription drugs dispensed at retail pharmacies. Similar to Part B, the Part D inflationary rebate provision holds manufacturers financially accountable when the prices of their covered drugs rise faster than inflation. This provision is a notable expansion of federal drug pricing controls into the outpatient retail market, impacting a broader array of pharmaceutical products and presenting both financial and operational challenges for manufacturers.

Eligibility under Part D is broader than under Part B, encompassing all covered outpatient prescription drugs provided through Medicare Part D plans, including both brand-name and biologic drugs. A key eligibility criterion is that the drug must be a Medicare-covered Part D product with sufficient historical sales data to establish a baseline pricing quarter. Unlike Part B, which is focused on physician- administered drugs, Part D rebates apply to drugs filled at retail or mail-order pharmacies and reimbursed through Part D sponsors or pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). The rebate applies when the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) increases at a rate that exceeds the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

AMP is a well-established metric used in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program to represent the average price paid to manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs distributed to retail pharmacies. However, for the purpose of calculating inflationary rebates in Part D, CMS has indicated that it may refine the methodology or adopt a similar, adjusted pricing benchmark more tailored to Medicare’s unique distribution channels. Until final guidance is issued, manufacturers should closely monitor CMS updates and consider modeling rebate exposure using AMP as a baseline, while preparing for potential adjustments based on future regulatory clarification.

The rebate amount for Part D drugs is calculated on an annual basis and is structured as follows:

Inflationary Rebate Amount = (Annual AMP_current – AMP_inflation-adjusted) × Part D units sold

Where:

- AMP_current is the drug’s average manufacturer price for the current year,

- AMP_inflation-adjusted is the baseline AMP adjusted for cumulative inflation using the CPI-U index, and

- Part D units sold refers to the number of units reimbursed by Medicare Part D plans in the given year.

The baseline AMP is established using pricing data from October 2022 or the first year of market entry, consistent with the IRA’s implementation timelines. If the current year’s AMP surpasses the inflation-adjusted baseline, the manufacturer must pay the difference multiplied by total Medicare Part D utilization. These rebates are paid to Medicare and do not directly affect plan sponsors or pharmacy reimbursement but are intended to reduce overall Medicare spending and potentially lower premiums for beneficiaries.

Several important exclusions and exceptions apply. Generic drugs are currently excluded from the inflationary rebate provisions under Part D, a policy choice that aims to avoid discouraging low-cost generic competition. Similarly, new products are exempt from rebates until a full calendar year of pricing data is available to establish an AMP baseline. CMS also has the authority to exclude drugs in shortage or to make adjustments in cases where rebate obligations could disrupt supply or patient access. Coordination with other federal programs, such as Medicaid and the 340B program, is also essential to avoid duplicate rebates and reporting inconsistencies. As it stands, CMS has declined to finalize its methodology for excluding 340B units for Part D inflationary rebates but noted that the agency is exploring ways to address this challenge. The agency plans to establish a Medicare Part D claims repository for removal of 340B units from Part D rebate calculations starting on January 1, 2026.

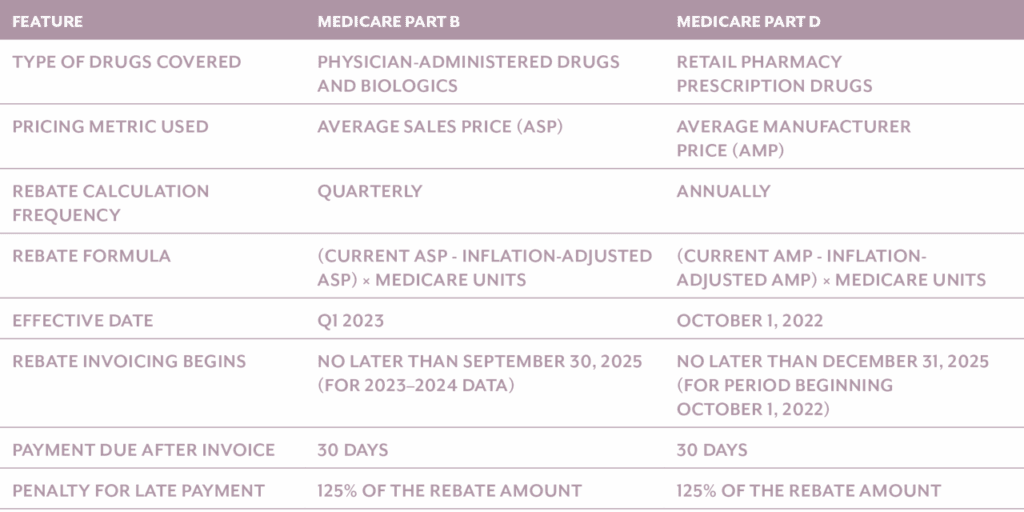

Table 1, below, provides a side-by-side comparison of the important differences of inflationary rebates based on whether the drug is a Part B or Part D drug.

Table 1. Comparison of Medicare Part B and Medicare Part D Inflationary Rebates

Considerations for Drugs in Shortage or Facing Supply Chain Disruptions

The Inflation Reduction Act incorporates flexibility in its inflationary rebate provisions for both Medicare Part B and Part D to account for drugs that are in shortage, experiencing severe supply chain disruptions, or deemed likely to enter a shortage. Recognizing that rigid application of rebate penalties during critical supply challenges could jeopardize patient access to essential therapies, the legislation allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to waive or adjust rebate obligations under certain circumstances. This safeguards the availability of high-need products and balances cost containment with the broader imperative of public health access.

For both Parts B and D, a drug may be temporarily excluded from rebate assessments if it is listed on the FDA’s Drug Shortages database or determined by CMS to be at risk due to significant manufacturing, distribution, or raw material challenges. CMS will monitor the FDA drug shortage lists, so there is no process for requesting rebate reductions for drugs in shortage, however, manufacturers can request a rebate reduction for drugs they believe are experiencing severe supply chain disruption or are likely to be in shortage. The Secretary has discretionary authority to withhold or modify rebate obligations in such cases, particularly if enforcing rebates could exacerbate shortages, reduce market availability, or disincentivize production during a vulnerable period. This flexibility is especially critical for sterile injectables, oncology products, and other high-complexity drugs that are prone to manufacturing constraints.

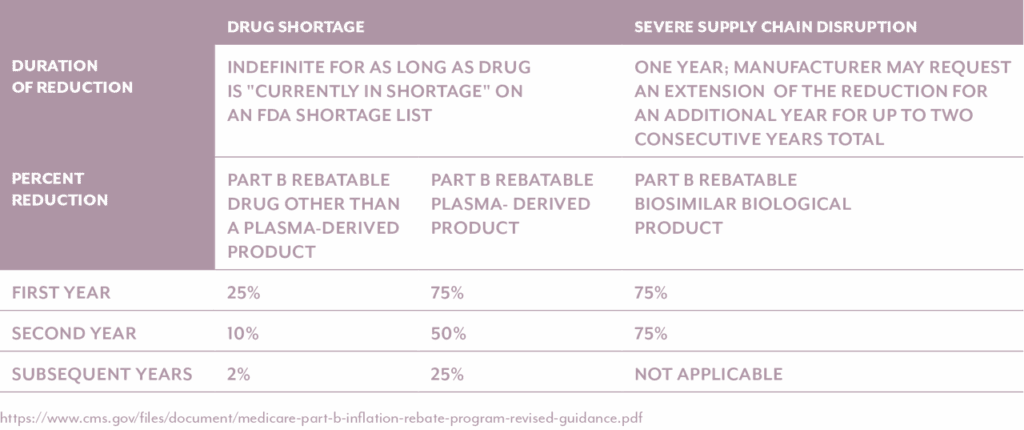

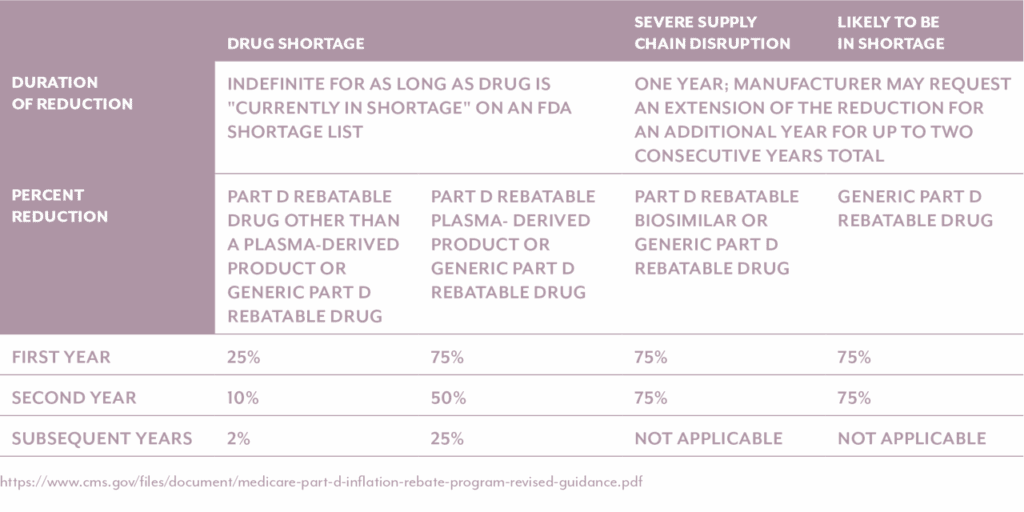

Both Medicare Part B and Part D take into account a variety of conditions when determining if a rebate reduction is allowable and the calculation of such reductions (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. Calculation of Medicare Part B Rebate Reductions

Table 3. Calculation of Medicare Part D Rebate Reductions

It’s important to note the above two tables differentiate between plasma-derived products and non-plasma derived products. CMS is distinguishing plasma-derived drugs from non-plasma-derived drugs in its implementation of the Medicare Part B Inflation Rebate Program due to the unique characteristics and vulnerabilities of the plasma supply chain. Plasma-derived therapies—such as immunoglobulins, clotting factors, and albumin—are produced from human plasma, which requires a labor-intensive collection and manufacturing process that cannot be rapidly scaled. The market for these therapies is also highly concentrated, with only a few manufacturers supplying critical treatments for rare and chronic conditions. These factors make the plasma product supply chain more susceptible to disruption.

To mitigate the risk of access issues, CMS has opted to increase the rebate reduction percentage for most plasma-derived products. This decision follows stakeholder feedback and concerns that applying inflationary rebates to these therapies could discourage production, limit availability, and ultimately harm patients who rely on them. By making this distinction, CMS aims to uphold the goals of the Inflation Reduction Act—namely, controlling drug price inflation—while protecting the stability of essential treatment supply for vulnerable populations.

In practical terms, manufacturers of drugs experiencing severe supply chain disruption or are likely to be in shortage may request a waiver or exception through a defined CMS process, supported by documentation such as supply chain analytics or third-party assessments. These exceptions are expected to be time-limited and subject to regular review. The process requires manufacturers to email CMS and submit either the Severe Supply Chain Disruption Rebate Reduction Request or the Likely to be in Shortage Rebate Reduction Request form. For drugs facing severe supply chain disruption, the form is due within 60 days from the first day that the natural disaster or other unexpected event occurred. For drugs likely to be in shortage, the form is due before the start of the applicable period in which the generic part D rebatable drug is likely to be in shortage. If the reduction is granted, the reduction will be in place for one year, and manufacturers may request extensions of the reduction for an additional year.

Ultimately, the policy of rebate reductions aims to ensure that the inflationary rebate framework does not unintentionally disrupt access to medically necessary therapies during periods of supply instability.

Rebate Payment Logistics

While the Inflation Reduction Act outlines how inflationary rebates are calculated under Medicare Parts B and D, it is equally important for manufacturers to understand when these provisions take effect and how and when rebate payments must be made. Although the inflation rebate formulas are straightforward, the timing of implementation, invoicing, and payment carries operational implications that manufacturers must plan for proactively.

Medicare Part B

Inflationary rebates under Medicare Part B went into effect for calendar quarters beginning on or after January 1, 2023. These rebates apply to single-source drugs and biologics whose Average Sales Price (ASP) increases faster than inflation. While the rebate liability accrues quarterly beginning in 2023, the actual invoicing and collection of payments is deferred. Per CMS guidance, the Secretary of Health and Human Services has exercised the statutory authority to delay invoicing for all Part B quarters in 2023 and 2024 until no later than September 30, 2025.

For future periods, CMS will issue a Preliminary Rebate Report no later than 5 months after each applicable rebate quarter.

Once received, manufacturers will have 10 days to challenge CMS’ rebate amount. Within 6 months of each rebate quarter, CMS will issue an actual Rebate Report, which will serve as the official invoice. Once invoiced, manufacturers will have 30 days to remit payment to CMS.

Failure to pay the required rebate amount within this 30-day window may result in civil monetary penalties (CMPs) equal to at least 125% of the outstanding rebate amount. While formal agreements between manufacturers and CMS are not required for the program, CMS has indicated plans to issue further rulemaking to define the penalty process and any accompanying procedural protections.

Medicare Part D

Inflationary rebate provisions under Medicare Part D technically became effective for applicable periods beginning on or after October 1, 2022, as defined in the statute. The first annual rebate invoices will be generated by CMS in 2025, based on 2022 and 2023 pricing and unit data. Manufacturers will be expected to remit full payment of the invoiced amounts within the designated timeframe.

For Part D, CMS will issue a Preliminary Rebate Report no later than 8 months after each applicable rebate period. Once received, manufacturers will have 10 days to challenge CMS’ rebate amount. Within 9 months of each rebate period, CMS will issue an actual Rebate Report, which will serve as the official invoice.

As with Part B, manufacturers that fail to make timely payments under Part D will be subject to penalties. While CMS has not yet finalized enforcement protocols, companies should begin preparing now by establishing internal processes for rebate calculation validation, payment scheduling, and audit readiness.

To ensure readiness, manufacturers should establish a rebate operations calendar and integrate CMS milestones into enterprise budgeting, financial planning, and compliance workflows. Aligning cross-functional teams—finance, pricing, legal, regulatory, and IT—around these timelines will help reduce the risk of late payments and penalties while improving audit preparedness.

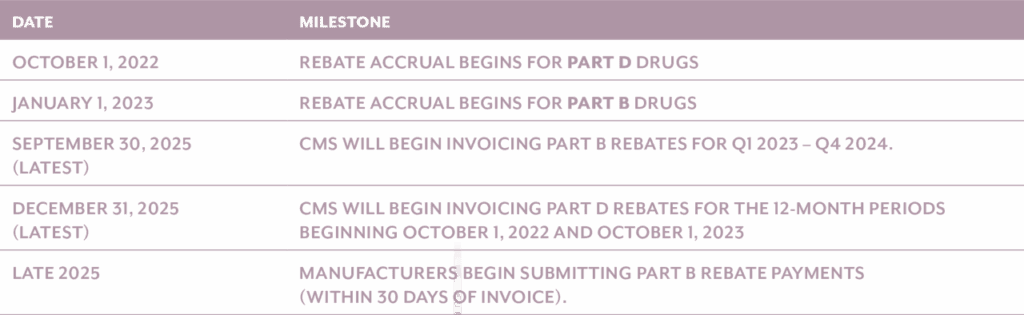

Key Implementation Dates and Timeline

Intersection with State Price Transparency Reporting

As pharmaceutical manufacturers adapt to the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) inflationary rebate provisions at the federal level, they must also remain vigilant about a parallel movement at the state level: State Price Transparency Reporting (SPTR). Over the past several years, a growing number of U.S. states—including California, Oregon, Vermont, Nevada, and Colorado—have enacted drug price transparency laws that require manufacturers to report price increases, new drug launches, and justifications for cost changes. These state-level mandates, while distinct in purpose and scope from Medicare inflationary rebates, reflect a broader trend toward greater regulatory scrutiny of drug pricing practices.

Similarities in Handling Price Increases

Both the IRA and SPTR frameworks are grounded in the objective of discouraging excessive drug price increases. Each requires manufacturers to track and report pricing behavior with a high degree of precision and timeliness. Specifically:

- Triggering Events: Both frameworks use a defined price change threshold to determine reporting or rebate liability. For example, SPTR laws in several states require reporting when a wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) increases by more than a certain percentage (e.g., 10% or more in a calendar year). In contrast, the IRA requires rebate payments if a drug’s ASP or AMP increases faster than the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

- Focus on Historical Pricing Benchmarks: Each framework relies on price comparisons against a historical baseline—whether that’s prior year WAC in SPTR or baseline ASP/AMP in IRA inflationary rebate calculations.

- Documentation and Oversight: Both SPTR and IRA rebate provisions demand comprehensive documentation and audit readiness. Manufacturers must substantiate pricing changes and maintain records that can be submitted to state agencies or CMS upon request.

Key Differences in Purpose and Enforcement

Despite shared characteristics, SPTR and IRA inflationary rebates diverge significantly in their structure, scope, and impact:

- Enforcement Mechanism: The most critical difference is what happens after a price increase. Under the IRA, price hikes above inflation result in mandatory financial penalties—in the form of inflationary rebates paid to Medicare. In contrast, SPTR laws are disclosure-based: they require justification of price changes but do not impose automatic financial consequences unless a state pursues separate legal or regulatory action.

- Scope of Drugs and Payors: SPTR laws typically apply to all commercially marketed drugs within a state’s borders, while IRA rebates apply specifically to Medicare-covered drugs under Parts B and D. This creates overlapping but non-identical compliance burdens, with different drug populations and payer channels in scope.

- Reporting Frequency and Format: SPTR deadlines and templates vary by state and may require semiannual or annual reports, often submitted through state-specific portals. IRA rebate obligations, by contrast, are standardized at the federal level with quarterly (Part B) and annual (Part D) calculations, governed by CMS submission guidelines.

Impact of Inflationary Rebates on Government Pricing Metrics

In addition to state price transparency considerations, there are also government pricing considerations. Recent CMS guidance—including Manufacturer Release No. 117—clarifies that the rebates paid under both §1847A(i) (Part B) and §1860D-14B (Part D) of the Social Security Act are explicitly excluded from Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) and Best Price (BP) calculations under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). This exclusion ensures that rebate payments to Medicare, which function more as compliance penalties than commercial discounts, do not directly affect the determination of Medicaid rebate liability.

Despite the exclusions, pharmaceutical manufacturers must exercise caution, as indirect impacts on government pricing may still arise. Strategic responses to minimize exposure to Medicare inflationary rebates—such as offering greater discounts in the commercial or 340B channels—can inadvertently create new, lower Best Prices or depress AMP, thereby increasing Medicaid rebate obligations. Furthermore, beginning in 2026, the Maximum Fair Price (MFP) established under the IRA for selected drugs will be included in Best Price, adding another variable that could drive down BP benchmarks and significantly affect rebate calculations across federal programs.

Government Pricing (GP) teams within pharmaceutical companies should proactively evaluate the downstream implications of IRA-related rebate liabilities on GP metrics. This includes ensuring internal alignment between pricing, finance, and contracting functions to monitor the ripple effects of commercial pricing adjustments. Enhanced GP analytics capabilities, scenario modeling, and cross-functional reviews are critical to safeguarding against unintentional GP consequences that could erode profitability. Additionally, GP teams must stay current with evolving CMS guidance and be prepared to incorporate MFP into Best Price calculations starting in 2026. In this evolving landscape, a coordinated and forward-looking approach is essential to manage the compliance and financial implications stemming from the IRA’s inflationary rebate provisions.

Implications for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and How to Address Them

Strategy

The IRA’s inflationary rebate provisions introduce new strategic constraints for pharmaceutical manufacturers. The law retroactively applies financial penalties on Medicare-utilized drugs that experience price increases above inflation, measured by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). For manufacturers, this disrupts long-standing commercial models that relied on routine price adjustments, particularly for legacy brands or products nearing the end of exclusivity. Additionally, high-cost therapies and those with growing Medicare utilization now carry heightened strategic risk due to their potential for outsized rebate liabilities.

The rebates also challenge strategic portfolio planning. Manufacturers with broad pipelines across both Medicare Part B and Part D must now consider inflation exposure alongside traditional pricing, access, and reimbursement dynamics. Market entry strategies, including launch sequencing and channel mix, must now be reevaluated through the lens of rebate sensitivity. Any delay in aligning internal decision-making with IRA pricing restrictions could lead to margin compression or missed opportunities to optimize net revenue.

To navigate these challenges, pharmaceutical companies should embed inflationary rebate considerations into cross-functional strategic planning. Pricing governance should include thresholds for inflation-aligned increases and rules for evaluating the timing of any adjustments relative to Medicare reporting cycles. Teams responsible for product lifecycle management and portfolio investment should be trained on how rebate dynamics interact with broader commercialization and market access decisions.

Equally important is proactive policy engagement. CMS retains broad discretion in interpreting rebate exceptions, particularly around terms like “supply chain disruption” and “shortage,” which can influence whether rebates are reduced. Manufacturers can protect their strategic interests by participating in rulemaking processes, submitting formal comments, and joining trade associations that advocate for industry-friendly interpretations. Long-term strategy should also involve forecasting how future CMS guidance could affect rebate exposure, especially for small-molecule and specialty products. This forward-looking approach ensures manufacturers remain agile, compliant, and resilient as the policy landscape evolves.

Finance

The financial consequences of Medicare inflationary rebates are both material and difficult to predict. Because rebate obligations are based on utilization volume and pricing benchmarks indexed to CPI-U, even modest price increases can result in large financial penalties for high-utilization drugs. These liabilities are calculated retroactively and apply at the unit level, making them especially punitive for manufacturers with growing Medicare market share. Additionally, companies managing drugs across both Part B and Part D face compounded financial exposure due to differences in calculation methods and market structures.

Budgeting becomes increasingly complex under these rules. Traditional financial planning models that focus on gross-to-net or price-volume tradeoffs may underestimate the rebate drag unless they incorporate real-time CPI tracking, Medicare utilization forecasts, and scenario-based modeling. Furthermore, the possibility of mid-year CMS guidance changes or revisions to rebate calculations creates uncertainty that is difficult to account for in fixed planning cycles. This volatility not only affects revenue forecasting but also limits flexibility in margin management and capital allocation.

Manufacturers must modernize their financial planning and analysis (FP&A) frameworks to reflect the IRA’s unique pricing constraints. At a minimum, companies should adopt integrated forecasting tools that combine drug-level pricing histories, CPI trend projections, and estimated Medicare claims data to simulate rebate exposure. These tools should allow teams to model multiple pricing strategies—e.g., annual increases versus static pricing—and assess how each approach impacts potential rebate liabilities under different utilization scenarios. Output from these models should directly feed into P&L forecasts, portfolio reviews, and business development evaluations.

To support this enhanced financial rigor, companies should synchronize rebate forecasting with quarterly CPI updates and CMS reporting cycles. This ensures that rebate accrual estimates remain relevant and actionable, especially as manufacturers make real-time pricing decisions. Central finance teams may also need to develop rebate-specific dashboards and key performance indicators (KPIs) to track emerging liabilities by product, channel, or payer segment. Lastly, collaboration between finance and compliance is essential to verify that reported prices align with the actual inflation thresholds used in calculations. With these capabilities in place, manufacturers can build financial plans that are not only resilient to regulatory shocks but also optimized for long-term sustainability.

Operations

The operational impact of inflationary rebate provisions is far-reaching, touching everything from supply chain management to commercial execution. Inflation penalties are influenced by Average Sales Price (ASP) or Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) metrics, which in turn can be affected by backend discounting, distribution timing, or even the way a product is packaged. Manufacturers must now assess whether routine operational decisions—such as adjusting wholesaler terms or launching new NDCs—could unintentionally increase rebate exposure.

Coordination across departments has become more critical than ever. For example, if a manufacturer implements a price increase without aligning it with Medicare utilization timing or supply chain availability, they could trigger rebate liabilities that might have been avoidable. Likewise, any disruption in production that leads to shortages can interact with rebate reduction criteria, creating potential compliance pitfalls or financial ambiguity. Fragmented or outdated processes can result in misaligned data, incorrect reporting, and missed opportunities to minimize exposure.

To address these complexities, manufacturers must invest in cross-functional alignment and integrated operating models. This begins with establishing new standard operating procedures (SOPs) that detail how price changes are communicated and executed across pricing, supply chain, and commercial operations. Manufacturers should also reexamine their channel strategies and discounting practices—especially with wholesalers, specialty distributors, and PBMs—to minimize unintended ASP or AMP volatility. Close monitoring of inventory levels and distribution timing is essential to ensure that price increases align with Medicare utilization patterns.

Internal controls and real-time data sharing will be critical to success. Operations teams should be equipped with forecasting tools that integrate pricing and utilization data, enabling them to model how supply chain shifts impact rebate risk. Manufacturers should also implement rebate-specific performance reviews to track how operational decisions influence exposure. By cultivating agility and data transparency across functions, companies can reduce rebate liability while preserving operational efficiency. Moreover, aligning incentives between commercial, finance, and regulatory teams helps ensure that operational execution supports broader compliance and financial objectives.

Technology

Managing the complexity of IRA inflationary rebates is not feasible without a robust technology infrastructure. Many pharmaceutical companies still rely on siloed systems or manual workflows that make it difficult to reconcile sales, pricing, and utilization data across Part B and Part D. These limitations hinder accurate rebate forecasting, inflate compliance risk, and reduce visibility into real-time exposure. Furthermore, CMS reporting requirements demand precision and audit readiness—two areas where legacy systems often fall short.

Another major challenge is the integration of disparate data sets. To accurately model inflationary rebates, companies need to consolidate data from ERP systems, pricing platforms, sales databases, Medicare claims, and CPI indices. Without centralized, validated data sources, manufacturers risk making rebate calculations based on outdated or incomplete information. This could lead to underpayment penalties, failed audits, or reputational harm.

Technology upgrades must be a priority for manufacturers aiming to comply with and mitigate inflationary rebate risks. Modern ERP platforms, when integrated with pricing and sales data, can provide a centralized source of truth for rebate calculations. These systems should be configured to automate tasks like rebate accrual tracking, CPI benchmarking, and CMS submission preparation. Advanced data analytics platforms can supplement ERP systems by enabling real-time rebate forecasting, visualization dashboards, and scenario modeling tools that help stakeholders quickly identify high-risk products or emerging liability trends.

Beyond automation, manufacturers should invest in data governance frameworks that ensure pricing and utilization data are accurate, current, and audit-ready. Tools that support reconciliation across federal programs—such as 340B, Medicaid, and Medicare—can help prevent duplicate rebate obligations or pricing inconsistencies. Establishing a centralized compliance repository that includes rebate documentation, CMS correspondence, and audit trails ensures manufacturers are prepared for external review. As the rebate program evolves, manufacturers will also need scalable and flexible systems that can accommodate future CMS rule changes or additional rebate reporting requirements. In this environment, technology is not just an enabler—it is a compliance imperative.

Conclusion

The Inflation Reduction Act’s inflationary rebate provisions mark a historic shift in Medicare drug pricing policy, introducing mandatory penalties for price increases that outpace inflation. While these provisions aim to protect beneficiaries and reduce federal healthcare spending, they also introduce substantial financial, operational, and compliance burdens for pharmaceutical manufacturers. As outlined in this white paper, the complexities of rebate calculation, reporting timelines, regulatory oversight, and cross-program coordination require a comprehensive response from the industry.

To succeed in this evolving environment, manufacturers must adopt proactive strategies that include robust financial modeling, integrated compliance controls, scalable technology infrastructure, and ongoing engagement with regulators and policymakers. With careful planning and cross-functional alignment, companies can not only mitigate risk but also position themselves to adapt to future reforms in drug pricing. The Inflation Reduction Act is not just a compliance challenge—it is a catalyst for manufacturers to modernize their pricing strategies, strengthen operational agility, and lead responsibly in a more regulated and value-driven healthcare market.

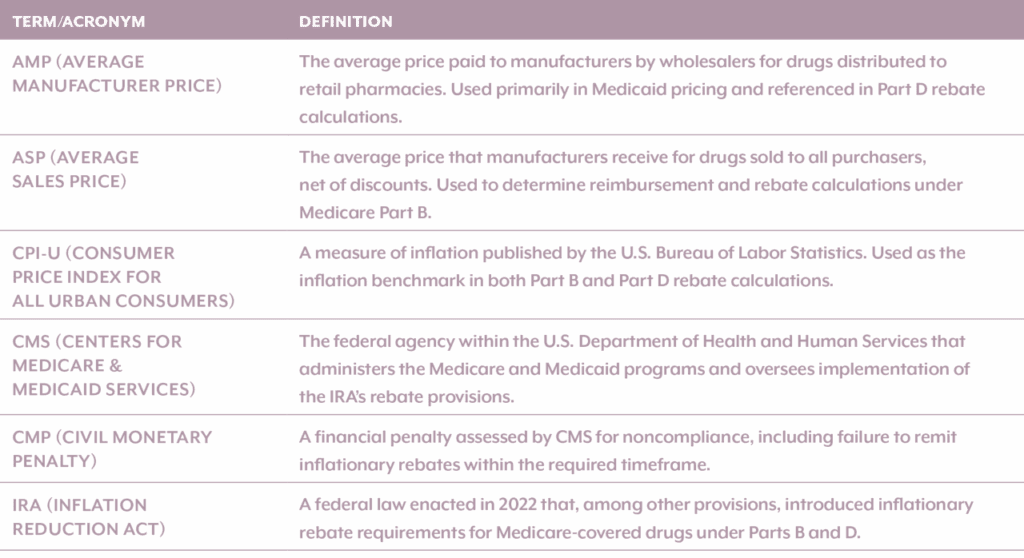

Appendix A: Key Terms and Acronyms