By Amber Daly

IRA & Drug Price Negotiation Program Background

What is the IRA?

Inflation hit historic highs, beginning in 2021 and carrying into 2022, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the Biden Administration, having just taken office in 2021 was forced to address rising costs for the Federal Government as well as millions of Americans.

One of the ways the Administration worked to address these issues was to introduce and eventually sign into law, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022. This piece of legislation provisioned significant funding across several sectors and programs (beyond healthcare), investing in initiatives that would eventually lead to cost savings for the Federal Government and consumers alike.

One of the key areas of focus within the IRA is broadly referred to as Drug Pricing Reform. Under this umbrella, funding was established to the tune of $288B1 to make improvements to Medicare. Within the IRA, there are 4 main components related to Drug Pricing Reform, including: Medicare Part D Improvements, Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, Inflation Rebates in Medicare, and Changes to Medicare Part B.

In this first installment of our white paper series on IRA, we’re tackling all things Drug Price Negotiation and Maximum Fair Price which is a key component of the price negotiation.

What is the Drug Price Negotiation Program?

Federal drug expenditures in 2022 reached upwards of $400B, with 22% of the costs traced back to just 10 drugs.2 Over the last several decades there have been numerous pieces of legislation introduced at the federal and state levels aimed at containing prescription drug costs, but till now, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was statutorily prohibited from directly negotiating drug prices. With the passing of the IRA, Medicare Drug Price Negotiation (or as we’ll refer to it throughout this paper as MFP – Maximum Fair Price) grants authority to CMS to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers. This establishes legally binding price ceilings, or Maximum Fair Prices, for selected Part D and Part B drugs that are high-expenditure, single source drugs without generic or biosimilar competition.

The primary objectives of establishing these MFPs include:

- Cost Controls: By negotiating lower prices for high-expenditure drugs, CMS aims to decrease the financial burden on the Medicare program and taxpayers, and ensure the sustainability of the program long-term

- Patient Affordability: The negotiated prices are designed to lower out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries, particularly those requiring chronic or high-cost treatments

- Price Transparency: By formalizing the negotiation process, the program seeks to create a more transparent system where drug prices reflect clinical value and production costs

As the Drug Price Negotiation Program is very much in its infancy, it will remain to be seen whether these objectives are met.

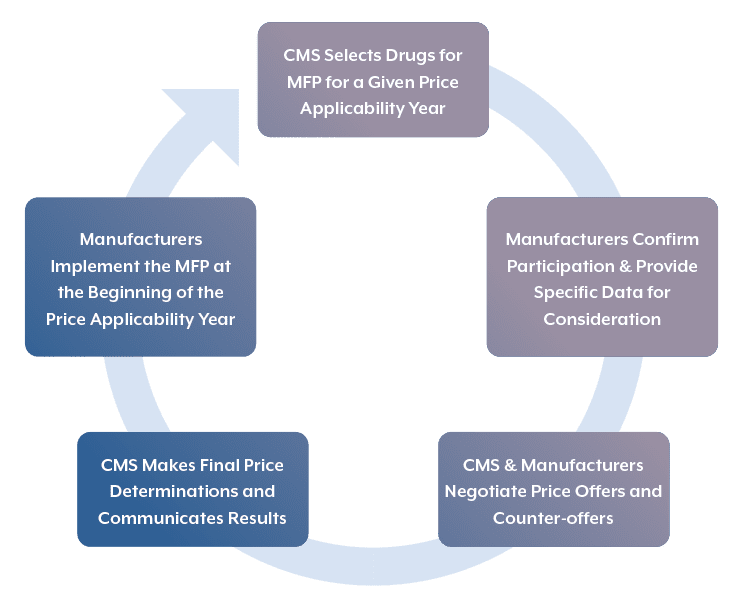

MFP: Price Negotiation Process

Before Medicare and patients can realize any benefits from the Drug Price Negotiation Program, there are many steps and an almost year-long process that will occur each year to select, negotiate, finalize, and enable the effectuation of the MFPs.

Drug Selection Summary

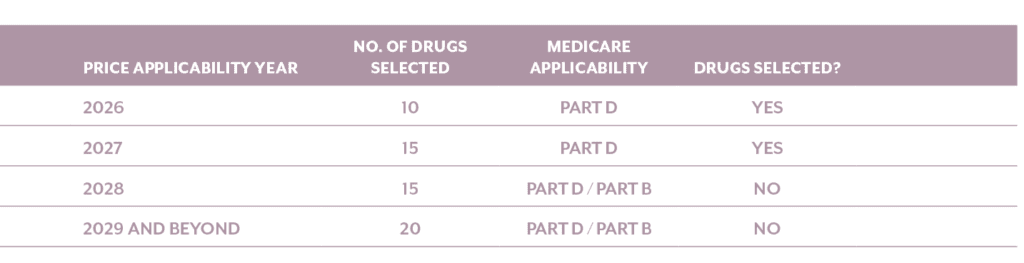

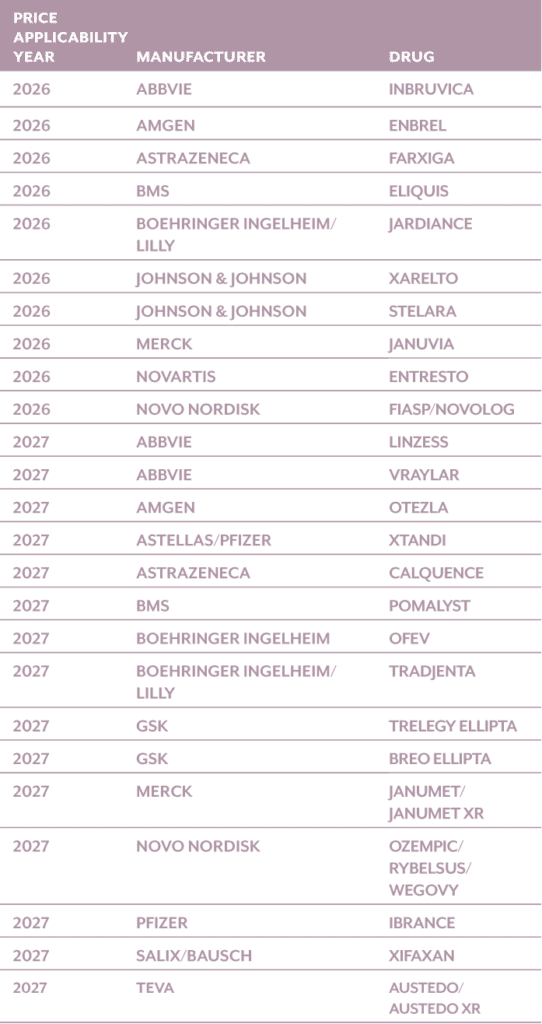

The first step in the negotiation process is for CMS to identify and communicate its plans for drugs included in the price applicability year under review. Each year beginning in 2026 a new set of MFP drugs will be active, expanding the program in number of drugs as well as the parts of Medicare impacted over time. To date, CMS and manufacturers have only completed one full round of the selection and negotiation process, however, the second round is upon us in 2025.

CMS analyzes prescription drug event (PDE) data to determine total expenditures for negotiation-eligible drugs under Part D. And from that data the top 50 drugs with the highest Part D expenditures are ranked and evaluated based on the following criteria:

Drug Type and Market Exclusivity:

- Small-Molecule Drugs: Eligible if approved by the FDA more than 7 years prior and without generic competition

- Biological Products: Eligible if licensed by the FDA over 11 years ago and lacking biosimilar competition

Exclusions:

- Orphan Drugs: Drugs designated for a single rare disease or condition under section 526 of the FD&C Act, with no other approved indications

- Low-Spend Drugs: Drugs with less than $200 million in combined annual expenditures under Medicare Parts B and D

- Plasma-Derived Products: Biological products derived from human whole blood or plasma, as indicated on their labeling

Additional Selection Considerations:

- Small Biotech Exception: Manufacturers can apply for an exception if a drug represents a significant portion of their revenue and meets specific criteria

- Biosimilar Delay: If a biosimilar is expected to enter the market imminently, the reference biological product may be excluded from negotiation

- Bona Fide Marketing: CMS conducts ongoing assessments to determine whether meaningful competition exists, ensuring that any generic or biosimilar products are marketed on a bona fide basis

Drugs meeting the above criteria have been selected for Price Applicability Years 2026 and 2027, depicted in the table below:

Once CMS makes its selections, manufacturers have a short window to sign agreements confirming participation in the program. While this step offers the illusion that the program is voluntary, failure to participate is likely to result in extreme consequences. The penalties are so significant they would push much higher costs to patients, limit patient access, and stifle revenue growth, almost guaranteeing, by design, a manufacturer’s participation.

Penalties Include:

- Civil monetary penalties calculated as ten times the difference between the price charged and the MFP, multiplied by the number of units sold

- Significant excise taxes starting at 65% of the product’s U.S. sales and increasing by 10% each quarter, up to a maximum of 95%

- Withdraw of a manufacturer’s portfolio from Medicare and Medicaid programs

Price Negotiation & Setting

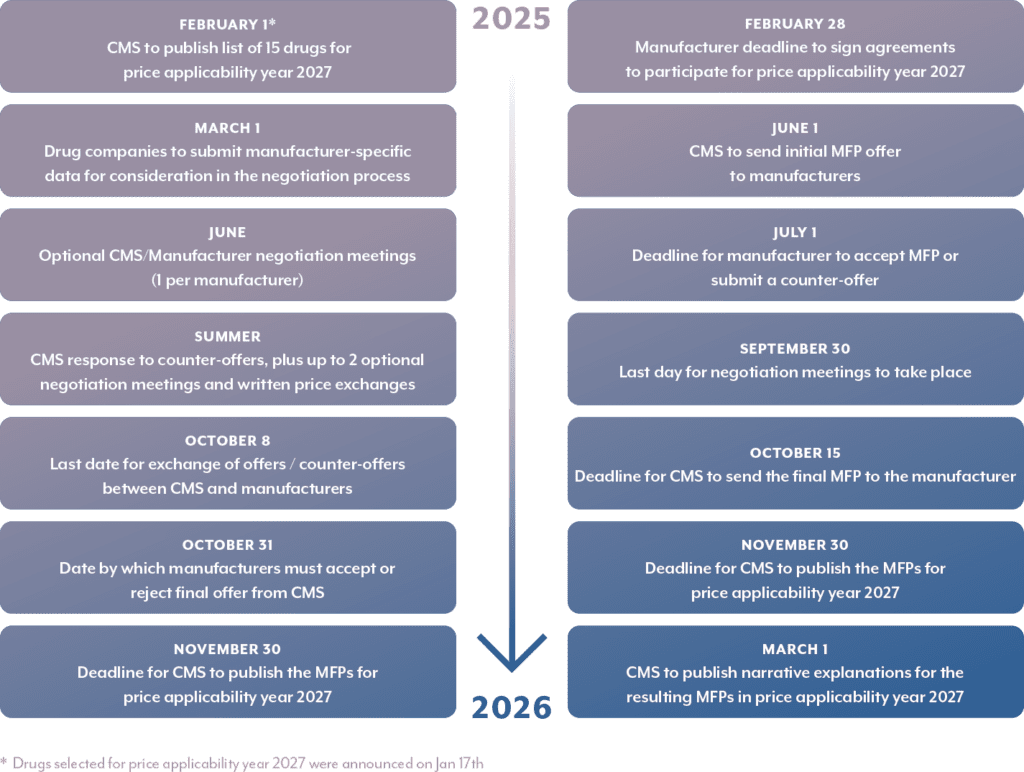

When drug selection is complete for a given price applicability year, the price negotiation process towards the MFP starts immediately.

Manufacturers must act quickly once they are made aware their drug(s) has been selected for the Program. They must first confirm participation by entering into an agreement with CMS to negotiate prices. And secondly, they must prepare supporting drug-specific data submissions including research & development costs; production & distribution costs; federal financial support for drug discovery and development; patent and exclusivity information, including pending and approved patents, FDA exclusivities, and FDA applications; and market, revenue, and sales volume data. As updates or revisions to the data become necessary, the manufacturer must report them to CMS in a timely fashion throughout the negotiation period.

Once the information is provided, CMS will host public engagement sessions with patient-focused roundtables and town hall meetings. During this period, the manufacturers will also have an opportunity to discuss their data submissions directly with CMS.

All of the information gathered till this point is taken under consideration while CMS derives their initial offer. Fortunately for manufacturers, there are some guardrails in place to ensure the MFP is “fair”. The Program sets an upper limit for the MFP, determined by the lowest of the following:

- Part D drug: Enrollment-weighted negotiated price (net of all price reductions, including rebates)

- Part B drug: Average sales price (the price paid by non-federal purchasers in the U.S., including rebates, excluding Medicaid rebates)

- Non-FAMP: A percentage of the non-federal average manufacturer price (the price wholesalers pay manufacturers for drugs distributed to non-federal purchasers). The percentage of non-FAMP varies based on the years since FDA approval or licensure:

- 75% for small-molecule drugs and vaccines 9-12 years after approval

- 65% for drugs 12-16 years after approval or licensure

- 40% for drugs more than 16 years after approval or licensure

Once CMS determines the price and sends the initial offer, it’s off to the negotiation races! Hopefully by this point manufacturers have had time to engage market access, legal, finance, and other commercial and government operational teams to work on forecasts and simulations designed to inform decisions they may make based on the offer received. Since the Program is so new and with much of the negotiations taking place behind closed doors, there do not seem to be any clear patterns, strategies or paths forward, to ensure the most favorable outcome for a manufacturer (remember, one of the previously mentioned objectives of the program is…transparency).

Now that price negotiation Round 2 is about to begin, there are some return players from Round 1 that have the advantage of experience on their side. Will they employ similar negotiation strategies, or will their approach become more or less aggressive based on the outcome in Round 1? And the new players for Round 2 are not only strategizing against what CMS might do, but also against how their experienced competitors will conduct themselves during the negotiations.

Throughout the negotiation process, the goal is for CMS and the manufacturer to reach an amicable MFP, however, if an agreement is not reached within the designated timeframe, CMS has the authority to unilaterally set the MFP. After the final price is determined and announced, the manufacturer has approximately one year to implement processes and tools to effectuate the MFP at the start of the Price Applicability Year.

A summary of the second round of drug price negotiation activities and timelines for Price Applicability Year 2027 is captured below:

MFP Effectuation

So CMS has determined the final MFP for your drug, now what?

With the first round of MFPs in effect beginning January 2026, the first 10 manufacturers have until September 1, 2025 to determine which effectuation option they will operate under and how to implement it within their current Pricing & Contracting operational landscape. This is a critical step for manufacturers with selected MFP drugs, given the penalties for non-compliance as mentioned above. It also represents an added layer of complexity to a manufacturer’s pricing & contracting operations, with additional burden across people, process, data, and technology.

CMS has provided two effectuation options for manufacturers to ensure the MFP is made available to dispensing entities. We’ll examine both options holistically, including the differences between them and pros and cons of each.

- Prospective Effectuation: The MFP is applied upfront at the package level, ensuring that entities purchase drugs at the reduced price at the time of sale

- Retrospective Effectuation: The MFP is applied after the sale at the unit level, where price adjustments are refunded back via rebates, based on the actual acquisition cost

Each option carries operational, financial, and compliance implications, as well as potential conflicts with 340B, Medicaid, and commercial contracts.

Prospective Effectuation

Prospective effectuation ensures that the MFP for eligible drugs is honored as an on-invoice discount where the MFP is extended at the time of invoice.

Key Characteristics:

- Pricing Level: MFP applied at the saleable package level

- Timing: The price adjustment happens upon the payment of the invoice

- Operational Considerations:

- Updating contract pricing structures with supply chain partners

- Communicating pricing changes in advance to ensure correct pricing is applied

- Ensuring wholesaler and distributor compliance in passing through the MFP. If multiple price points exist for a single dispensing entity, how will a wholesaler/ distributor know to honor an MFP vs. 340B vs. Commercial Payer price without knowing at the time of sale, the intended program or recipient?

- Dispensing entities must manage separate inventories for MFP purchased drugs, to ensure the correct price is applied based on eligibility

- Master Data Management overheard to create/ manage accounts for all dispensing entities as customers in their revenue management & ERP systems to ensure MFP eligibility is communicated throughout the supply chain

Pros

- Simplifies program compliance, eliminating the need for retrospective rebate adjudication & settlement in a short cycle time of 14 days

- Relies on existing infrastructure, operating a model similar to common chargebacks processing that happens against contracted pricing for other customer types/programs

- Eliminates cash flow concerns for dispensing entities, providing real-time discounts

Cons

- Heavy burden on manufacturers and wholesalers to manage master data and contract changes as well as increased chargeback processing volumes

- Potential pricing conflicts with 340B and Medicaid due to overlapping price reductions that become challenging to retroactively resolve once the price is already honored

- Dispensing entities to carefully monitor inventory to ensure the MFP purchased drug is being dispensed to the intended program recipient (without oversight, there is a lot of room for error)

- Lack of standard identifiers to communicate MFP-specific transactions which can result in incorrect extended pricing throughout the supply chain: Manufacturer > Wholesaler > Dispensing Entity > Patient, and could ultimately result in noncompliance and associated consequences for manufacturers

- Package pricing and sales data doesn’t align exactly to utilization, therefore requiring conversions to ensure the right price

- Practically speaking, the lack of transparency in the claim and sales data to create a connection point linking an eligible patient to given price point at the time of invoice, is practically impossible, calling into question whether this ‘option’ is even possible

Retrospective Effectuation

Retrospective effectuation is the process by which manufacturers will retroactively calculate refunds in the form of rebates to dispensing entities based on utilization claim data.

Key Characteristics:

- Pricing Level: Applied at the unit level where adjustments are made based on actual acquisition cost, unites dispensed and the MFP

- Timing: Refunds for the difference between acquisition cost and the MFP occurs after the drug is dispensed and must be paid within a 14-day window

- Operational Considerations:

- Implement processes and technology solutions to ingest the claim data from dispensing entities via the MTF (described below), scrub and validate the data, calculate the rebate amount, and process payment

- Claims calculated using SDRA (Standard Drug Rebate Amount) which is based on WAC, however, that may not represent the actual acquisition cost if there are other eligible contract prices

- Rebates must be remitted to dispensing entities within 14 days to mitigate dispensing entity cash flows concerns. Typically, manufacturers have 30-45 days to process other commercial and government rebates. Given the volume of transactions and the data validation required, this may require increased headcount on the manufacturer side to ensure compliance. It allows for minimal time to resolve disputes

- Manufacturers must determine how to establish payment remittance – either using MTF PM (described below), or another mechanism. If the MTF PM is not utilized, claim level payment details must still be submitted to the MTF DM

- If a manufacturer determines to remit payments outside the MTF PM, they must also keep record of debit/credit activity to facilitate reversals or adjustments to claims . A process for handling disputes with individual dispensing entities must also be established, in the event the manufacturer chooses to not enroll in the MTF PM

- Need a way to determine cross-program and dual-patient eligibility to correctly calculate the rebate amount (e.g. Inflation Rebates, Commercial/Medicaid/ Medicare/340B overlapping eligibility)

- To anticipate MFP impacts on Gross-to-Net, manufacturers will need to re-assess rebate accrual rates and forecasting models to account for the impact of MFPs from changes in pricing, volume/utilization, and rebate liabilities. Current models and strategies for forecasting Best Price, Medicaid, 340B liabilities may also need to be adjusted for any unintended cascading impacts from the MFP

Pros

- Enables due diligence on the manufacturer side to validate claims data and dispute before payment is extended, providing a bit more control over the release of funds

- Manufacturers can maintain existing contracts with various supply chain partners

- Tools, services, and capabilities already exist in the marketplace that leverage similar processes to ‘lift and shift’ to MFP Rebate Processing

Cons

- High administrative burden / cost to process, either requiring technology solutions to support or 3rd party providers to process on a manufacturer’s behalf

- Medicaid SDRA methodology may misalign WAC-MFP vs. acquisition-based rebates

- Potential Medicaid best price conflicts, depending on how acquisition costs are calculated for rebates

- Aggressive 14-day turnaround time, beginning when the MTF DM sends the claim-level data. If timelines are not met and identified via an audit or complaint, CMS will investigate and potentially levy civil monetary penalties equal to ten times the difference between the price paid and the MFP, multiplied by the total number of units dispensed

What is the Role of the MTF in MFP Effectuation?

The MTF (Medicare Transaction Facilitator) is a centralized system established by CMS to facilitate the implementation of the Drug Price Negotiation Program. Its primary purpose is to ensure the accurate application of the MFP for selected drugs under Medicare.

The MTF is structured into two distinct modules, each serving a specific function:

Data Module (MTF DM)

- Function: Facilitates the exchange of data among stakeholders, including pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), manufacturers, and CMS including the following:

- Claim-level data confirming dispensation of drugs to MFP-eligible individuals

- Initiates the 14-day prompt payment window

- Rebate payment elements, including payment confirmation and amount

- Includes the Standard Drug Rebate Amount (SDRA), calculated as WAC minus MFP

- Generates Electronic Remittance Advice (ERA) for payments processed through MTF PM

- Mandatory Participation: All manufacturers of drugs selected for price negotiation are required to participate in the MTF DM to ensure proper data flow and compliance

Payment Module (MTF PM)

- Function: Manages the financial transactions related to MFP effectuation, such as:

- A fund transfer mechanism for manufacturers (electronic and paper check)

- A credit/debit ledger system for tracking MFP refunds, reversals, adjustments, and claim revisions

- Payment tracking for manufacturers who opt to make payments outside of MTF PM

- Optional Participation: Manufacturers have the discretion to participate in the MTF PM. If they opt out, they must establish alternative mechanisms to handle the financial aspects of MFP effectuation

Data Exchange and Privacy

The MTF handles sensitive information, including drug pricing details, transaction records, and beneficiary data. CMS has implemented protocols to ensure that all data exchanges comply with applicable privacy and security regulations, safeguarding the information managed by the MTF. Data that will be passed includes (but not limited to):

- Drug Identifiers (NDC, Package Level Data, etc.)

- Transaction Details (Date of Sale, Dispensing Entity, Claim Number)

- Beneficiary Eligibility Status for MFP

- Pricing Information (WAC, Contracted Price,

- MFP Applied Price)

- Manufacturer Rebate Data (for retrospective effectuation)

Manufacturer Response to MFP and Looking Ahead

Since the enactment of the IRA, several pharmaceutical manufacturers have initiated legal challenges against the Drug Price Negotiation Program, particularly targeting the MFP provision. These lawsuits underscore the industry’s concerns over the constitutionality and economic implications of government-mandated price negotiations. Among the companies that have pursued litigation are Merck, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Astellas Pharma. Additionally, industry trade organizations such as the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and healthcare providers like the National Infusion Center Association have also challenged the law.

A central theme in these lawsuits is the argument that the IRA’s price negotiation framework constitutes an unconstitutional taking under the Fifth Amendment. Manufacturers argue that the requirement to accept government-determined prices for their products amounts to a form of price control that deprives them of their property rights without just compensation. Merck, for example, has explicitly stated that the law forces manufacturers to engage in what is effectively a “sham negotiation” process, where refusal to comply results in exorbitant penalties or exclusion from Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Another major contention is that the IRA’s framework infringes upon companies’ First Amendment rights by compelling them to endorse and participate in a pricing structure dictated by the federal government. This claim, raised by Merck and other plaintiffs, suggests that the law forces manufacturers to affirm a pricing scheme that they fundamentally oppose, thus violating their right to free speech.

Beyond constitutional challenges, pharmaceutical companies argue that the law disrupts market dynamics and threatens innovation. Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis have emphasized that price-setting mechanisms imposed by the government could reduce incentives for developing new therapies. By capping revenue potential for key blockbuster drugs, they contend that the IRA may disincentivize investment in research and development, particularly for therapies with high upfront costs and long development timelines.

While some lawsuits have faced early dismissals, multiple cases are currently on appeal, and new challenges continue to emerge. Just last month, the legal challenge by Novartis against the Drug Price Negotiation Program reached a crucial stage. Novartis’ case was previously dismissed by the New Jersey District Court in October 2024, which led to the company’s appeal. The Trump administration filed a defense in support of the IRA’s drug price negotiation provisions, agreeing with the legal arguments made by the previous government and the lower court, which had dismissed Novartis’ claims. The outcome of this and other legal battles will have significant implications for the future of pharmaceutical pricing, healthcare policy, and government intervention in the drug market. If courts uphold the IRA’s provisions, the Drug Price Negotiation Program could become a long-term fixture of U.S. healthcare policy, reshaping industry pricing strategies. Conversely, if manufacturers succeed in rolling back the law’s key provisions, it could set a precedent limiting federal involvement in drug pricing.

The trajectory of the MFP provision and the broader drug pricing framework will depend not only on the outcome of ongoing litigation but also on the political and regulatory priorities of the new administration. As stakeholders across the healthcare spectrum navigate this uncertain environment, proactive engagement in shaping policy and regulatory discussions will be essential to ensuring a sustainable balance between cost control, innovation, and patient access to life-saving therapies.

Looking Ahead

While much of this is not within a manufacturer’s full control, there are some things that are. Cross-functional organizational support and internal alignment is a critical success factor, whether a manufacturer is already selected for MFP or not. While it may be routine for pricing committees, brand teams, market access, P&C operations, finance, and legal to interact to implement and comply with existing regulatory policies, the depth of MFP extends beyond the provisions of the existing programs. Everyone across these teams holds an important seat at the table to: forecast in case your drug is selected for negotiation; have plans and responsible parties in place to ensure key timelines are met; have defined strategies for negotiation with comprehensive data and compelling arguments to substantiate counters with CMS; and ensure strong operational teams on the functional and technical sides are standing by to swiftly implement solutions to effectuate the MFP. However, even without being selected (yet), launch teams, brand strategy, market access, finance, and others must evaluate how actions and decisions across the commercialization continuum must be adjusted to offset or anticipate direct and indirect MFP impacts. MFP may seem self-contained to just one drug at a time, but its reach extends far beyond. And with a manufacturer beholden to so many stakeholders, it’s impossible for current ways of strategizing and working to stay entirely the same. The transformation will be significant.

Additionally, 2025 and 2026 will be pivotal years, not just as we track another round of price negotiations, but as manufacturers of the first 10 drugs will be put to the test to enable capabilities to support MFP effectuation. This group of manufacturers will be the early MTF adopters, the first to encounter any operational challenges or gaps not currently addressed in the guidance, and the first to potentially lobby for process adjustments or changes based on real-world experience. They are actively planning now to operationalize, as they must be ready come January 1, 2026

We anticipate much to evolve over the coming months and years with this program – with the new Administration and how they might run the program, or change it; resolution of ongoing legal battles and what that may mean for upholding current program provisions; insights once the MFPs are active and being effectuated and how initial plans to operationalize may need to be updated or modified; and real-world data & analytics to support claims on whether the original program objectives of Cost Containment, Patient Affordability, and Price Transparency are truly being met.

Sources

- “SUMMARY: THE INFLATION REDUCTION ACT OF 2022”,

Democrats.Senate.gov, https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/

inflation_reduction_act_one_page_summary.pdf ↩︎ - “Medicare Part D Spending By Drug”, Data.CMS.gov,

https://data.cms.gov/summary-statistics-on-use-and-payments/medi-

care-medicaid-spending-by-drug/medicare-part-d-spending-by-drug ↩︎